The Promise of Oak Restoration

One of the hardest things about this fire has been its impact on the trees. Yes, those of us who lost homes are grieving our homes, in our different ways. But we all share in the sadness of losing countless beautiful, beloved trees: many firs – including one that sheltered the ashes of a community founder; gorgeous oaks that graced our homes and barn; at least one maple – which always delivered a precious shock of vivid spring green or glowing autumn yellow as the year turned; and countless madrones and manzanitas, with their smooth tawny barks.

Some of these were lost to the Glass Fire itself; they toppled or charred as it moved through, or soon after. Some were declared hazard trees by PG&E or AT&T in the fire’s immediate wake, and were cut down. Some we have removed ourselves, as we know they will not recover. And PG&E is back on our land now, taking down trees they marked “P2” (Phase 2) that are in danger of falling on power lines. Later this year, we will engage a forester to manage salvage logging in some areas of our forest, taking out dead firs that can be used for lumber, reducing fuel load in the process.

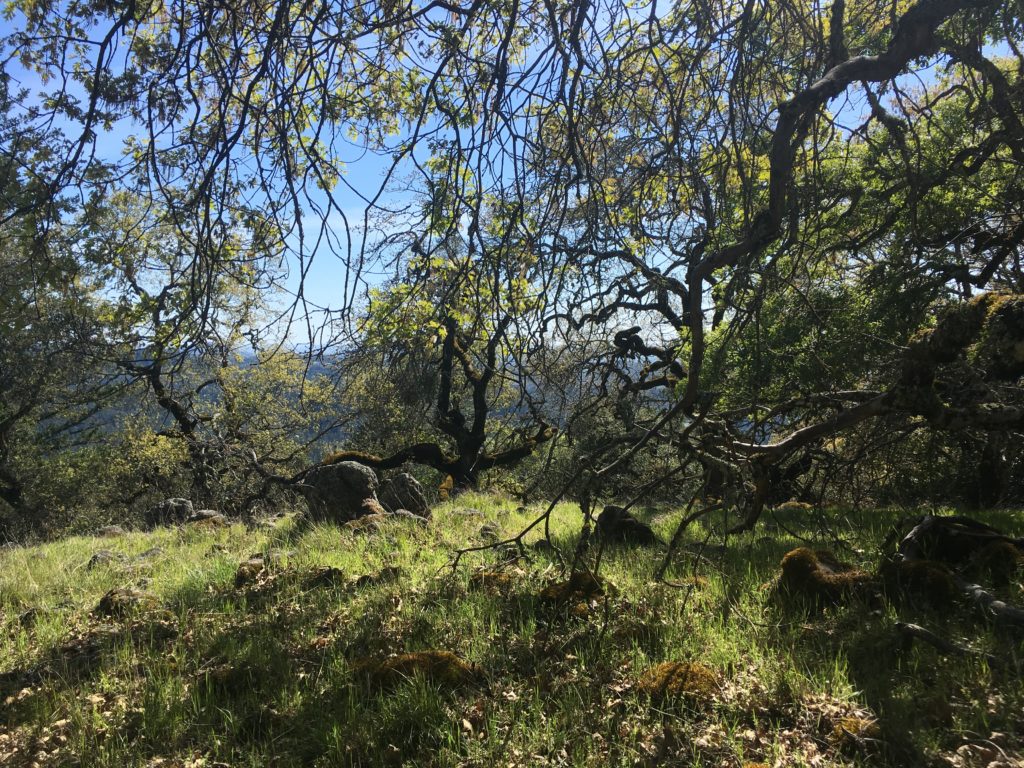

We know that there is so much work to be done to heal and restore and rejuvenate this landscape we tend. We need to be on the lookout for erosion, invasives, and impacts on the habitat of our non-human neighbors. Out of all of this, though, something beautiful is emerging: a commitment to oak restoration.

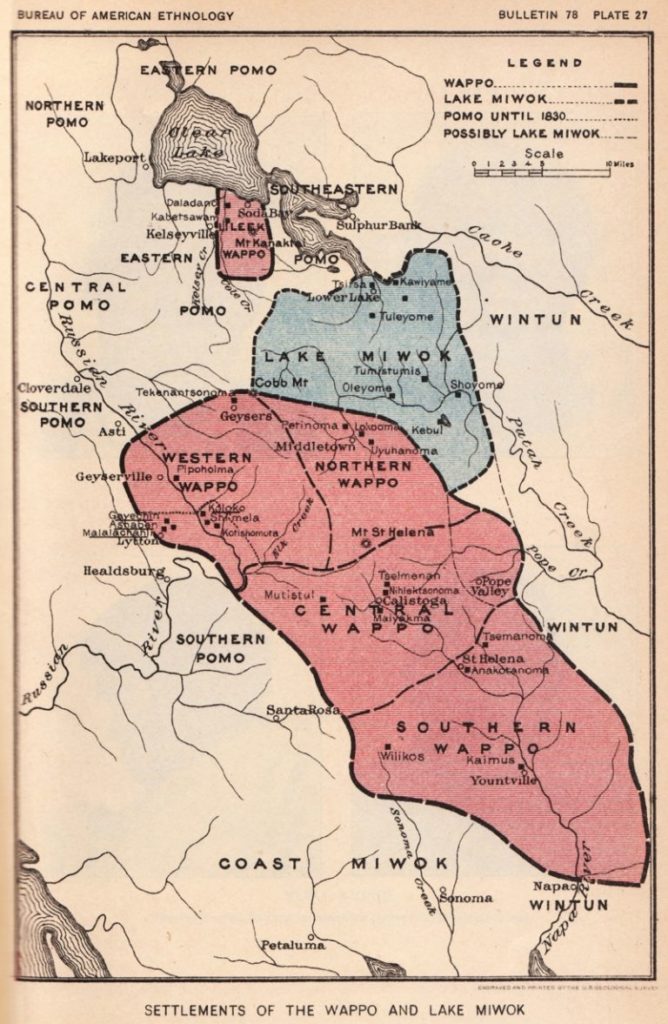

Thankfully we have so many local resources and leaders to turn to, in order to understand how to do this work. Pepperwood Preserve, our watershed neighbor, burned in the Tubbs Fire of 2017, and its scientists and educators have a lot to teach us. Recently, a few of us attended a Pepperwood webinar on the indigenous meaning and tending of black oaks, taught by Clint McKay, Pepperwood’s Indigenous Education Coordinator, a member of Pepperwood’s Native Advisory Council and of the Wappo, Pomo and Wintun communities. (Monan’s Rill is situated on the homeland of the Wappo / Onasatis people.)

The acorns of the beautiful black oak provide sustenance for the Onasatis people and many of their non-human siblings. In his teaching, McKay told us about Pepperwood’s Black Oak Project. They identified 60 healthy specimen black oaks and studied their microenvironment. In order to replicate this health in other trees, they conducted microburns, removed invasives, and thinned the forest. At Monan’s Rill we have done some of this kind of work, in partnership with the NRCS EQIP program and Fire Forward, and now the Glass Fire has given us an opportunity to rethink large swathes of our land. We know that “oak woodlands” in northern California do not usually look the way they did when they were stewarded by indigenous communities, and that our mountains in particular have experienced a long stretch of fir overgrowth and oak crowding. How can we use this moment of devastation to plant beauty, share resources more wisely, and cultivate a healthier relationship with the earth we walk upon?

Some of us will walk with Clint McKay at Pepperwood this spring, to learn about black oaks and other plants and trees important to our local indigenous communities. We are also in conversation with longtime oak arborist Dave Muffly, learning about oak propagation methods that we could use here at the Rill. All of this is happening in concert with our work with Friends of the Mark West Watershed and the Sonoma County Forest Conservation Working Group, striving for watershed health and large-scale vegetation management for fire safety.

This is undeniably a challenging time for us at the Rill, and we are buoyed by the vision of a healthier forest and planet. We are humbled by what we continue to learn about indigenous land stewardship practices. We are nourished by the promise of oak woodland restoration.

p.s. You can support our work on oak restoration, and community restoration more broadly, through our GoFundMe donation page. Thank you so much!